BECAUSE OURS COULD BE THE BEGINNING OF A BEAUTIFUL FAIRY TALE DREAMED OF FOR YEARS

Open Call 2020-2021

As a result of the Open Call announced in November 2020, Bilsart has provided production support to Mustafa Boğa’s video project in respect to the evaluation of the selection committee.

Mustafa Boğa’s exhibition entitled “Because Ours Could be the Beginning of a Beautiful Fairy Tale Dreamed of for Years” will be at Bilsart on June 8 – 30!

Private lives, public phantasms

We came across the portfolios of the artists who responded to Bilsart’s open call, inclusive of Mustafa Boğa’s proposal, in last December and January, at the peak of both the winter and the shutdown. In a context where the future was suspended and public spaces were under curfew; at a time when we were confined in our domestic spaces to deal with the past, Mustafa was looking at his family’s archive, consisting mostly of video recordings of weddings, and proposed a project in which he searched for his own identity at the intersections of the private and public spheres : “But really who am I? Do I know that? Can I reach the answer by examining the random recordings of past weddings?”

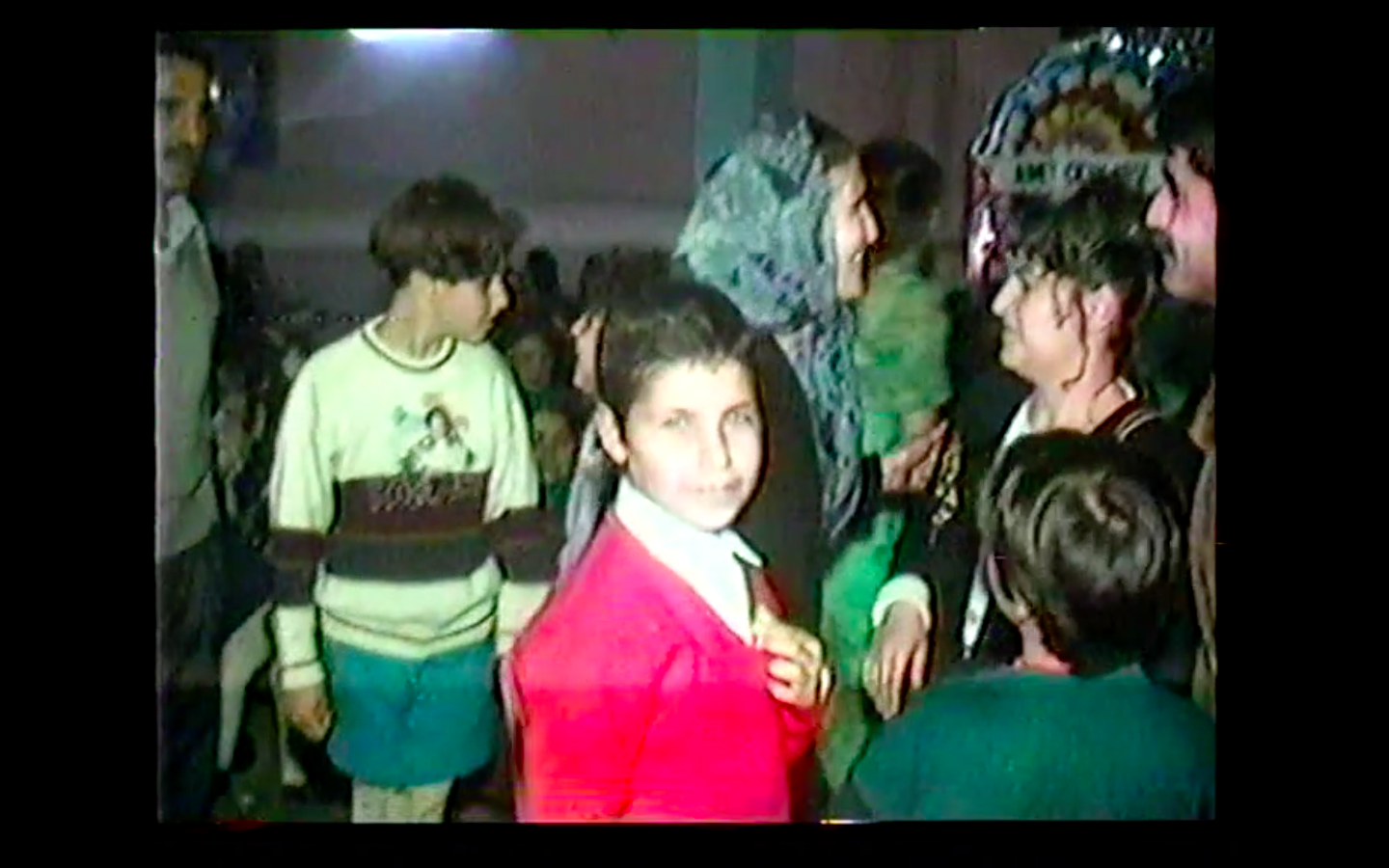

The family archive in question consists of wedding records that took place in the period between 1986 and 2018, in a region centered around Adana –which we can define as the hometown of Mustafa Boğa and his extended family-that also covers Mersin, Hatay and the Çukurova region. The 15-screen installation in the exhibition consists of sequences selected and recompiled as part of an artistic intervention and by the artist who also attended these weddings as a family member. Departing from this point, the installation proposes an experience of intimate, historical and public witnessing through the wedding as a performative social ritual and the recording technologies used in documenting this performative ritual that have evolved over time.

Homemade video recordings have an important place in the history of the twentieth century. In the twentieth century, 8mm film, which has been in personal use since the 1930s, became widespread in the 1960s with the Super 8 format; followed by the VHS and Betacam models across the technological spectrum in the late 1970s, during which family life, private lives and individual experiences were documented on an ever-growing scale and the visual archive of everyday life was created and stored for the first time to such an extent. In this exhibition, when we look from a distance of about 30 years, it is possible to point out a relationship between technology and aesthetics through the image texture and color scale of changing video techniques, and to observe that certain image technologies are identified with certain historical periods, social memory and collective affect: such as the intensity of red tones in the videos shot in the 80s, the over exposed light colors with harsh contrasts, or the noisy texture of the analog image, which coincides with the aesthetics of the early 1990s, which appears to us as “low resolution” in today’s common terminology.

While transforming his family’s 30-year-old wedding video archive into an artwork, Mustafa revealed a series of artistic gestures that he created by being inspired from both his own memory and all video recordings. On the one hand, he determined the unchanging choreography of the wedding ritual and reduced each ceremonial element (wedding, dance, gift collection, etc.) to the most performative moments by turning them into isolated sections from the records, and then by spreading these concentrated moments onto 15 screen setups, he offers us a new composition, almost an animation. On the other hand, he took sections shaped around the main characters, including himself, who are present at every wedding, and whom we have witnessed moments from the course of his life for 30 years. Among them, the artist himself is perhaps the easiest to recognize for the audience: Mustafa Boğa, who appears before us at a younger age than today, even when he was a child, looks at us through evasive eye contact over the camera, and through himself over the camera.

However, this new arrangement also opens up ways for us to touch a social and much more universal reality through video recordings of a family. As revealed by the title, we are faced with the wedding and the ideal of marriage as a ceremony that channels all expectations, desires and fantasies at the intersection of the personal and the social, and simultaneously, we look at the residual images that are left behind the advancing time, and as we look, we look at the births, deaths, divorces, growing up and getting old that pass through the wedding ceremonies. From this point, on the one hand, we arrive at the temporal scale of social reproduction, and on the other hand, we are faced with the merciless flow of time, as we are in a constant state of disintegration, loss and turning into dust, just like in pixelated images that lose data while being transferred from analog to digital.

In the video recordings we encounter as a whole, the differences in shooting techniques stand out beyond the image texture and transmission flaws. Moving and out-of-focus images in the earliest videos make the body and movements of the person holding the camera visible, and while recording and transferring the image almost as part of the ceremony, we come across camera and shooting techniques that make itself invisible in parallel with the increasing image resolution over time. We are moving from an amateur and participatory shoot to a professional and objective shooting technique, and more and more to a performativity that acts for the camera, aiming at the recording rather than the ceremony itself. These images also witness the birth of a self-discipline, the most striking example of which is in the selfie culture. From this perspective, wedding, as a personal and social ceremony, seems to hang between fantasy and imperative: as an increasingly industrialized and tightly coded space for entertainment and activity consumption, beyond bodies coming together and celebration, it calls for alignment with its own codes, and it emerges as a disciplinary tool in which image recording and appearance gains importance. Going one step further, it can be said that this ceremony, stretched between entertainment and imperative, points to a normative life in which norms such as nuclear family, heterosexuality and biological reproduction, which are resistant to change and still unquestioned in many regions, dominate through image today.

Having partially seen the selection made by the artist from the video archive in question, and writing this article on the exhibition plan, a desire arises to read this video installation together with a work of Mustafa that I know better. As in the “Adorned Dialogues” series that capture the floral wreaths, which are also ritual objects, and accompanying words, and establishes an extremely mischievous relationship between space and object; here, too, the artist is in pursuit of moments where the public and the private intersect and are inseparable. Although the artist seems to be chasing definitions of identity shaped around social games and rituals, actually the artist displaces the image and the object by working with a collage logic, interrupts the flow and re-assembles, with a dexterity that can pass from the most kitsch image to color and texture abstractions that make the medium itself visible, via extending to queer possibilities which leaves the question of identity itself cumbersome.

Text by Aslı Seven

ABOUT MUSTAFA BOĞA

The artist, who continues working in Adana and London, graduated from Harran University Department of Radio-TV Broadcasting in 2000. Following his BA studies, he graduated from Istanbul University, Department of Journalism in 2009 and received his first master’s degree on Cinematography and Post-Production at London Greenwich University. After working in film production companies for about 5 years, he worked on his second master’s degree at Central Saint Martins, Department of Fine Arts between the years 2014-2016.

Mustafa Boğa frequently focuses on the themes and rituals of the lands he grew up in: manipulated photographs of family members, wreaths we encounter at weddings and funerals, quilts embroidered with unusual motifs, images created with free embroidery technique give clues about the artist’s childhood spent in the south of Turkey. The artist who transforms his subjects into stories both emotionally and culturally, focuses on the power of the systems we are in that push us from one place to another.